“Hamlet”.

It could have been from a Noel Coward script or an Ealing comedy, but “Hamlet” was the code-word received by Major Haygarth, officer commanding of Expeditionary Forces Institute (EFI) Entertainments at 9am on Friday 10th May, 1940.[1] Sent via the War Office teleprint room by Basil Dean, it signalled the start of “Operation Z”, the evacuation of EFI personnel from forward areas entertaining the British Expeditionary Forces (BEF). It also signalled the end of the ‘phoney war’ that had seen stars like Gracie Fields, Leslie Henson, and George Formby provide entertainment to many of the bored troops waiting for something to happen. A period where entertainment had become not only important for the troops serving overseas but also their loved-ones waiting for news at home.

ENSA, referred to as EFI whilst serving in France, boosted the morale of the people at home as well as the troops serving overseas. Mass media, in the form of the BBC, had also entered the war and were keen to broadcast performances by some of Britain’s stars back to the civilian population at home. In November 1940, Gracie Fields performed two concerts in Douai and Arras, part of which was broadcast back home to the UK by the BBC.

According to Dean, “Gracie’s voice over the ether was like a Verey light piercing the fog of official censorship. It brought the human side of the war home to every listener and afforded one more striking example of the triumph of personality over red tape.”[2] Our Gracie was not everyone’s cup of tea; later in the war Spike Milligan described her “as funny as a steam roller going over a baby.”[3] But that was Spike. Entertainment was becoming an important link between the troops and home.

‘Hamlet’ triggered an evacuation plan that had been organised two months earlier when Basil Dean, the Director of ENSA, when he had last visited Major Haygarth at GHQ, Arras. Dean had been well prepared. On May 10th, there were 12 entertainment troupes (207 civilian performers) keeping troops chipper in forward areas, with parties such as “The Strolling Players” and Will Hayes’ “Empire Music Hall” moving around an area that was fast becoming a battlefield.[4] As well as variety shows, ENSA provided mobile cinemas, lectures (on topics like football), and sing-song units. Each mobile troupe or party had a maximum of 15 people (including a manager) and were assigned a bus and a 5-ton lorry for stage and props (which included their own piano). ENSA also operated 20 mobile vans carrying 16mm double projectors working in forward areas of the BEF, along with permanent cinemas in Arras, Lille, and Le Havre.[5]

Dean’s foresight in creating Operation Z was thanks in large-part to his previous experience with the army. During the First World War Dean had been instrumental in setting up many of the static Garrison Theatres located close to the front in his role as head of the Entertainment branch of the Navy and Army Canteen Board (NACB) of War Office Theatres.[6] Knowing that the nature of the military conflict in 1940 was likely to be much more mobile than the Western Front during the previous war, Dean had organised an evacuation plan should the front move suddenly. Operation Z would not remove all the EFI members from the continent, they had important work still to do but pulled them back to safer areas like Rouen. Discussing Operation Z with Major Haygarth in March 1940, Dean recalls the conversation as follows:

“We shall need a code word,” said the major. “What’s it to be?”

“Something theatrical, so that the signal doesn’t get mixed up with anything of a military nature. I suggest ‘Hamlet.’”[7]

By midday on 10th May, Major Haygarth had located and transported the 207 entertainers into holding areas, where they were given hot food and issued 72-hour dry ration packs. A lot of the smooth organisation was down to the precise bookkeeping of Virginia Vernon, who organised all the billets for the artistes in France at the time.

Ordering the sometimes rather highly strung artistes to move was easier said than done. As German planes flew over and strafed Lille, a star of British theatre and film, Will Hay, more usually associated with the absent-minded school master character, ignored the danger and flew into a rage at the afront of the invading forces. As Dean describes in his memoir, “he persisted in rushing up and down the street, shaking his first at the aircraft overhead and shouting violent oaths as he pocketed pieces of spent shell for souvenirs.”[8]

Mr Hay was eventually persuaded to calm down and loaded down with shrapnel, got on the Empire Music Hall truck and taken with his fellow artistes to the mustering points. By the evening of Friday 10th May, the ENSA performers were all safely installed in their new (safer) billets – again thanks to the organisation of Virginia Vernon.

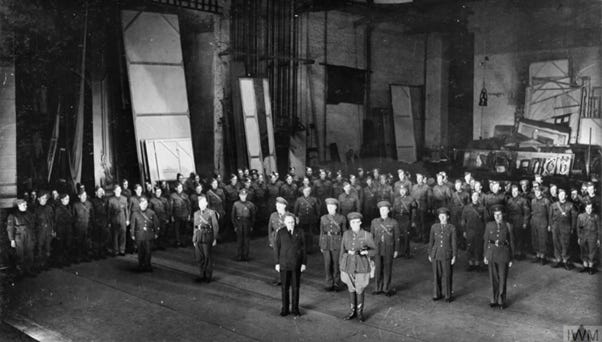

ENSA continued to entertain the troops in France for over a month longer with the Allies fighting a retreat. As the evacuation from Dunkirk unfolded in early June, Dean called all cinema owners in the South and West of England to open up their cinemas to entertain the troops arriving back home. On June 10th 1940, female artistes were ordered to evacuate France, but many of the male artistes and technicians, including mobile cinema units, continued on for another week. On June 16th 1940, Virginia Vernon noted in her diary that the last of the ENSA personnel departed France in a boat from Brest – a few days after Paris fell. On their return to Drury Lane later in June 1940, Basil Dean and the ENSA personnel who were evacuated from France took the following photograph, with Major Haygarth at the front.

Remarkably none of the civilian entertainers were lost or captured during this period, thanks in no small part to Basil Dean’s foresight and Virginia Vernon’s organisation. ENSA went on to fight another day.

[1] Basil Dean, The Theatre at War (London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, 1956), pp. 113–15.

[2] Dean, p. 78.

[3] Spike Milligan, Mussolini: His Part in My Downfall, 4 (London: Viking, 2012), p. 54.

[4] Richard Fawkes, Fighting for a Laugh: Entertaining the British and American Armed Forces, 1939-1946 (London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1978), p. 40.

[5] Dean, p. 85.

[6] Harry Miller, Service to the Services The Story of the NAAFI, 1st edn (London: Newman Neame Limited, 1971), p. 23; Tony Lidington, ‘Don’t Forget the Pierrots!’: The Complete History of British Pierrot Troupes and Concert Parties (Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2023), p. 233.

[7] Dean, p. 114.

[8] Dean, p. 115.

Nice work Matt. Currently reading James Holland’s Stanley Christopherson book of his memoirs and he refers to the mobile cinemas in Africa quite a lot. Clearly even that helped!

I wrote a short piece on the use of cinemas last month that may be of interest - https://open.substack.com/pub/matteatonmedia/p/delivering-a-few-hours-of-escape?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=20360b