Don’t Let’s Be Beastly to the Germans

The portrayal of Germans and Germany in wartime entertainment

Having watched two great Leslie Howard films recently, I was struck by the differences in their portrayal of Germans and Germany. This got me thinking about how British entertainment dealt with the topic of the enemy during the Second World War. This is by no means an exhaustive analysis, but I wanted to provide a few examples to show a gradual hardening of opinion as the war progressed. But we start with Neddie Seagoon in the desert…

Harry Secombe and the Royal Artillery marched into Carthage in May 1943 to the tunes of ‘Roll Out the Barrel’ and Strauss played by a regimental band. The musicians and instruments belonged to the recently captured band of the Hermann Göring Jäger Division. In Arias and Raspberries, Secombe admits, ‘none of us could really believe it was happening”.[1] The band must have been good as they popped up all over the place. The 5th Northampton’s enjoyed a ‘wembley-style’ accompaniment by the German band when they played the East Surreys at a football match on the Tunisian coast.[2] Not long afterwards, the front page of the British army newspaper, Tripoli Times featured a photo of the German band entertaining Nazi prisoners of war as they went to the cages.

Was this really so surprising given that both sides fighting in North Africa adopted Lili Marlene as their own song? The culture of Britain and Germany had more in common than one might think. Shakespeare was performed in German theatres through the war and the works of George Bernard Shaw were very popular with German audiences.[3] The Allies in 1943, however, were still a long way off defeating Germany and it was not in their interest to feel too much empathy towards their enemy. Prompted by a noted softening of stance towards our Teutonic brethren from what he called the ‘moralists and sentimentalists’, Noel Coward sang, Don’t let’s be beastly to the Germans. It was performed on the BBC in July 1943 and the lyrics warned against letting our guard down, sarcastically claiming, “let’s try to bring out their latent sense of fun” and “now they’ve suffered defeat we mustn’t let them feel upset or ever get the feeling that we’re cross with them or hate them”.[4] Coward still received criticism for the song from some quarters taking his lyrics at face value!

From 1940, the British public had got used to laughing at the ridiculous German spy, Funf appearing on Tommy Handley’s It’s That Man Again (ITMA) radio show. The character’s tag line was “Zis is Funf, your favourite spy. I haf found out everyzing.” and provided a reason to laugh at the sinister broadcasts made by William Joyce’s Lord Haw Haw early in the war. Given the success of German spies in Britain during the Second World War, the portrayal of Funf was probably not far off the mark!

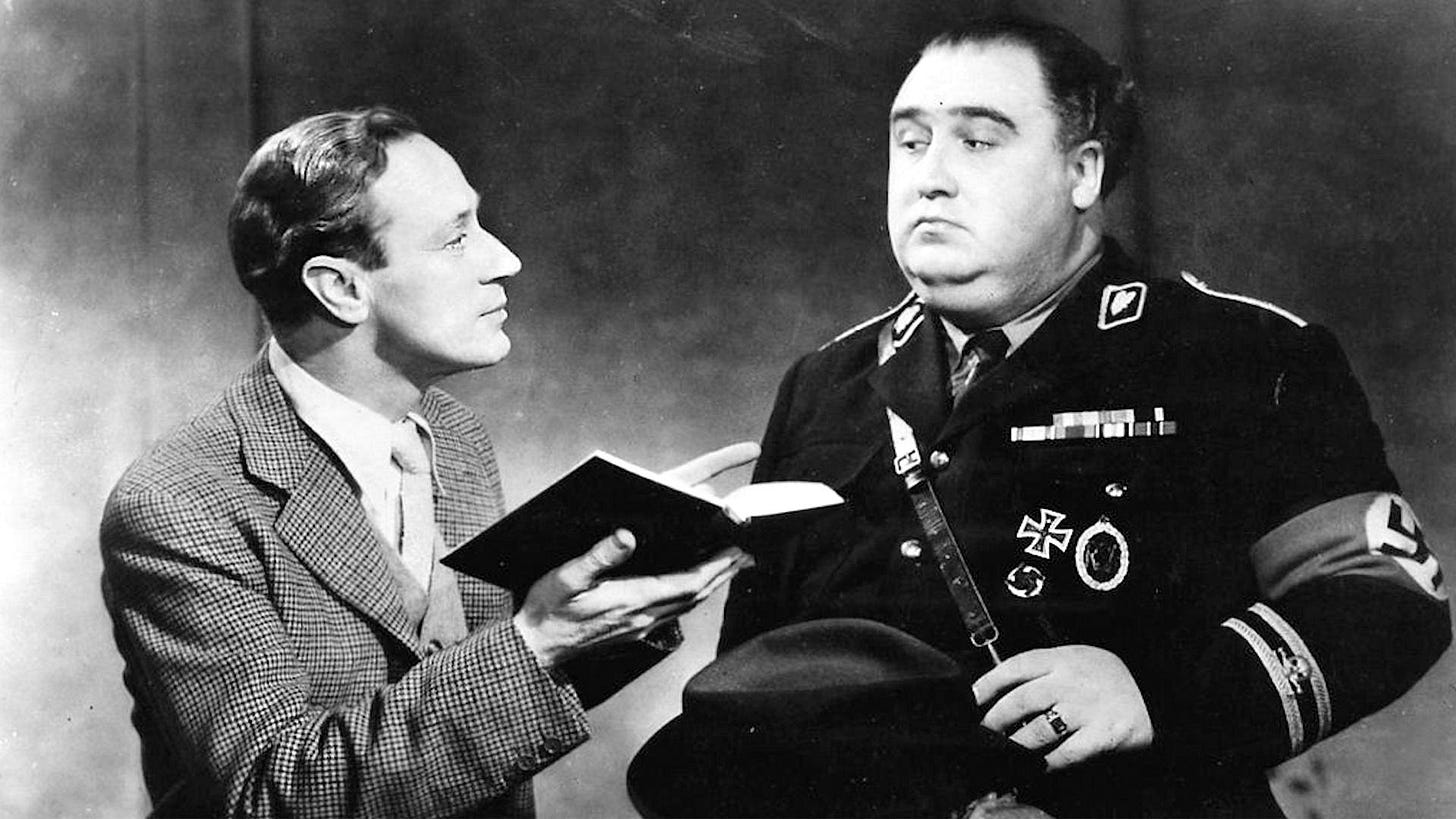

Whilst Coward’s 1943 song mentions Nazis, it is interesting that the lyrics are aimed at Germans and the wider Germany. This was very different to the portrayal of Germans vs Nazis in the 1941 Leslie Howard film, Pimpernel Smith.[5] Howard plays the seemingly absent-minded Professor Horatio Smith, who is actually responsible for freeing scientists, artists, and academics from Nazi prisons and concentration camps. Smith enlists the help of his Cambridge Anglo-American students and under the guise of an archaeological field trip, they thwart the evil plans of the Gestapo and help several people escape pre-war Germany. The baddies are easy to spot as they all have Nazi armbands, in contrast to the German civilians who are perfectly pleasant and amiable. On the eve of Germany’s invasion of Poland, an evil General von Graum (superbly played by Francis L. Sullivan) confronts Professor Smith, only to be subjected to a classic Leslie Howard dressing down:

“You will never rule the world because you are doomed. All of you who have demoralized and corrupted a nation are doomed. Tonight you will take the first step along a dark road from which there is no turning back. You will have to go on and on, from one madness to another, leaving behind you a wilderness of misery and hatred. And still you will have to go on because you will find no horizon, and see no dawn, until at last you are lost and destroyed. You are doomed…”

The audience is in no doubt that it is the Nazis who are doomed, not the German people.

A year later in Leslie Howard’s film, The First of the Few, there’s another pre-war Germany scene but the distinction is less pronounced.[6] Howard plays Reginald Mitchell, the inventor of the Spitfire (but most people agree Leslie’s performance was much more closely based on himself than the famous aeronautical engineer). Together with his test pilot, Crisp, played by a loquacious David Niven, they visit Germany in the early 1930s. Whilst watching gliders in Bavaria, someone helpfully explains that “the Versailles Treaty does not allow Germany to build engines.” They could have even used the same Alpine scenery as Howard’s Pimpernel Smith, but the locals are very different now. A Nazi (wearing an armband) shouts to get a civilian Oompa band into order and they all march off. Later in a traditional beer hall, behind a door marked private, the two characters played by Howard and Niven are treated to dinner by German officers. The contrast in this scene is between the British (wearing black tie) and the Germans (uniform and lounge suits). They’re introduced to Dr Messerschmidt, and it soon becomes clear that Germany wants to do away with the Treaty of Versailles, rearm and become the overlords as quickly as possible. Back in England, Mitchell, driven by a new urgency to defend his country, says “I want to build a fighter, the fastest and deadliest fighter in the world.”

These two films, both directed by Leslie Howard are only a year apart, but by 1942 perceptions can be seen to have changed. The national defeats experienced by Britain by this time, together with the bombing suffered by the civilian population the attitude towards Germans and Germany had hardened. This is supported in the special report published in November 1942 (although based on data from June 5th that year) by Home Intelligence on the ‘Public Feeling on Post-War Reconstruction’. Regarding the treatment of Germany, The report highlights the popular feeling that ‘we might be too lenient’ and that Nazi leaders should be punished. A very small minority thought that extermination or sterilization might be the answer, however more generally it was agreed that Britain should avoid victimizing the German people economically.[7] A year after this, Noel Coward’s Don’t Let’s be Beastly to the Germans was released, which left no room for sentimental feelings.

[1] Harry Secombe, Arias and Raspberries: An Autobiography (Fontana, 1990), p. 102.

[2] Eric Taylor, Showbiz Goes to War (Hale, 1992), p. 63.

[3] Anselm Heinrich, Entertainment, Propaganda, Education: Regional Theatre in Germany and Britain between 1918 and 1945 (University of Hertfordshire Press ; Society for Theatre Research, 2007), pp. 191–94.

[4] Don’t Let’s Be Beastly to the Germans by Noel Coward July 1943

[5] Pimpernel Smith, dir. by Leslie Howard (Anglo-American Film Corporation (UK), 1941).

[6] The First of the Few, dir. by Leslie Howard (General Film Distributors, 1942).

[7] Our People’s War: Home Intelligence Reports and the Monitoring of British Morale, June 1941-December 1944, ed. by Jeremy Crang (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024), pp. 675–76.

Hmmm. Whilst I agree that attitudes hardened I’m not so sure about your timescales Matt. You quote the release dates of films but maybe the more relevant date is when they were scripted and made, which would be earlier. In particular I believe that that there was a real hardening of mood during the blitz in the winter of 1940/41 . There are numerous contemporary references to demands to strike back and ‘give them some of their own medicine’ or similar - the line between Nazis and ‘other’ Germans is fading.