I was asked earlier this week why I started researching troop entertainment during the Second World War. Am I spending several years of my life researching this topic because I watched too much It Ain’t Half Hot Mum in my youth? Did I read too much Spike Milligan? Well, yes probably, but there’s a more personal reason.

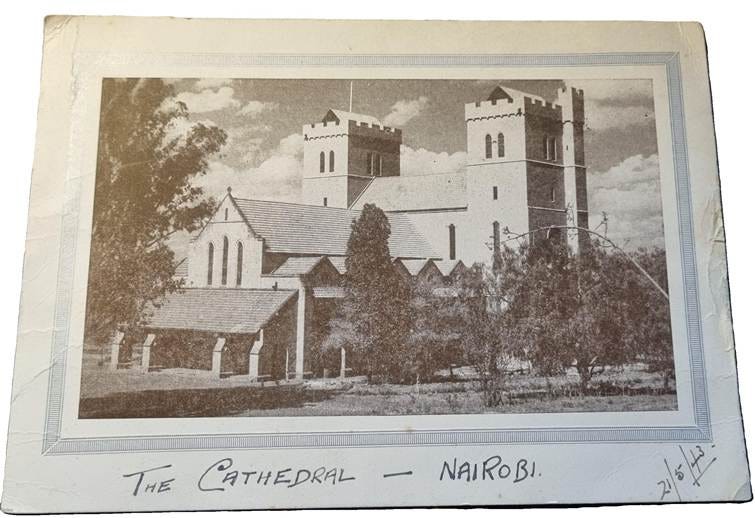

The most prized item in my Grandfather’s home was a biscuit tin stuffed with dog-eared sepia photos in no particular order. I used to spend hours sorting through this treasure trove, marvelling at the photos of far-away places and strange sights, that seemed like another world to rural Bedfordshire. Photos from Kenya, Egypt, and the Levant were mixed with newspaper clippings and servicemen’s guides to Aleppo and Cairo. They included the obligatory photos of my Grandfather in front of the Sphinx and the Pyramids of Giza, sitting on the waterfront at Alexandria, and stranger settings, like skiing among the cedars in Lebanon. These exciting, glamorous experiences reminded me of James Bond and must have seemed all the more incredible for a young man who had not travelled further than 10 miles from his Bedfordshire village before 1940.

Corporal Maurice Rowley was an accountant in the RAF, and, like many servicemen, he saw no action during the war. He was part of the long tail, dismissively referred to as bottle washers and pen-pushers by some popular historians (a trend I increasingly find disrespectful). In a world where the overblown contributions of individuals like Paddy Maine are worshipped on TV, Maurice Rowley’s service was quite unremarkable. He served abroad, away from his family for nearly five years, and made sure the paperwork for squadrons in East Africa was in order. This was something I learned relatively recently.

After his death I was interested in piecing together Maurice’s experiences from his typed memoir, diaries, letters, and newspaper clippings he kept. These serve as a reminder of how many ordinary people from rural backgrounds were thrust into unusual locations and had to get on with it during the war. You can see some of his collection as part of Their Finest Hour archive here: https://doi.org/10.25446/oxford.25923055.v1.

The story of Maurice’s wartime experiences told in his letters and diaries was in stark contrast to the glamorous photos I cherished so much as a child. The entries spoke of being homesick, bored, browned off, and occasionally feeling “Bloody Cheesed”! For many of the years spent away, he felt far from home and annoyed with the military authorities for its petty rules and punishments. The 21-year-old Maurice seemed obsessed with the speed with which letters arrived from Britain, which gives a clue to the importance he showed in maintaining a connection with his family at home.

His unhappy existence, however, was punctuated with moments of escape and entertainment featured strongly in his diary. There were regular cinema trips, especially in Nairobi or Cairo, as often as two or three times a week. An ENSA show performed by professional entertainers in the squadron’s dining hall was a significant event for Maurice in early 1943. In Kenya, the RAF often organised their own entertainment; he sang in the unit choir and saw service concert parties or pantomime shows. For many troops in the long-tail, organised entertainment provided an important link to home and a reminder of why they were fighting. Whilst maintaining morale, it was also a release valve from the perceived “bullshit” of military life and may have allowed many men to keep their sanity.

Organised entertainment was an important part of many servicemen’s wartime experiences. Moreover, our society’s memory of the war is bound up with the nostalgia songs from the Forties. I strongly felt that organised entertainment was a topic demanding more serious research. As part of my journey, I hope to uncover more about what entertainment meant to those servicemen in the audience. The magnetic attraction I felt towards that biscuit tin stuffed full of photos in my youth is now replaced by Army Welfare records, Morale reports, and War Diaries at Kew and stories of ENSA.