'Bastard’ Basil: Drury Lane’s Dictator?

“I am afraid that Mr Basil Dean rather tends to trail his coat on occasion.”

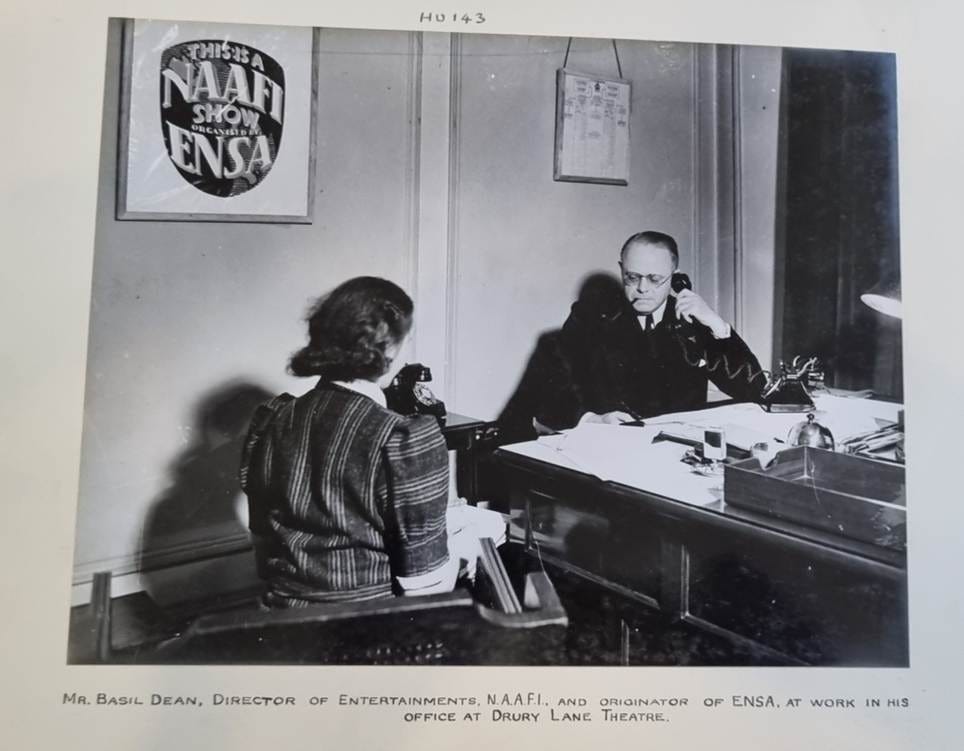

At the end of the war, Basil Dean (1888-1978), the Director of Entertainment National Services Association (ENSA), was accused of being a dictator and, more damagingly, of wasting public money. What was he like and what qualities allowed him to mobilise 80% of Britain’s entertainment industry for the best part of seven years?

Dean is remembered today for his contribution to the war effort and was rightly awarded a CBE in 1947. One of those people who thought they should have gone further and knighted Dean is Andrew Merriman, who describes his ‘confidence, force of character and determination, in conjunction with his knowledge and dedication to the entertainment world, provided him with the necessary ammunition to harangue the authorities.’[1] It is safe to say that without Dean, there would have been no ENSA. It is hard to imagine any other person being able to match his achievements, his ability to negotiate with the disparate showbiz interest groups and unions. Furthermore, not many people had the character and vision to impose their will on the NAAFI, the War Office, and the Department of Labour over such a long period. Perhaps George Black might have organised entertainment for the British Army in the absence of Dean, but it would not have been as ambitious as ENSA, which provided entertainment to all three Services and the civilian workers in the factories and mines on the home front.[2]

Before the war, Dean had built a fearsome reputation as a theatre producer and film studio owner, who launched the careers of George Formby and Gracie Fields with the forerunner of Ealing Studios. Noel Coward met Dean just after the First World War as a director in his twenties and thought him a ‘pimply, knobbly-kneed youngster with an assured manner’.[3] Ten years later, Coward noted Dean’s bullying manner with Jane Cowl and how he had earned a show business reputation as that “Bastard Basil”.[4] The great English film director, Carol Reed, admitted to Eric Ambler that the only two people he feared were the autocrats, Basil Dean and Ted Black, head of Gainsborough films.[5] To better understand Dean’s temperament, Jack Hawkins describes a nerve-wracking rehearsal in his early stage career.

“We were all pretty agitated, having heard some hair-raising stories of Basil Dean’s sarcasm and intolerence of sloppy acting. There was one particular legend of a leading man who was so cruelly flayed by BD’s tongue that he fainted on the stage. At this, Basil slipped on his coat, glanced at the unconscious actor, and said: ‘I think we will break for lunch.’”[6]

HR would probably want a word with Dean if he were working in the theatre today. Such an incident would not have surprised actors of the time. Joyce Grenfell talks of Dean’s ‘pinsized heart’ and Gracie Field’s step-daughter described him as simply, ‘a miserable bastard’ who ‘could be so nasty and spiteful’.[7] He didn’t suffer fools gladly, and in his line of work, Dean had to deal with a lot of clowns.

He’d built this reputation before he was 50 years old, but Hawkins adds,

“In spite of his sharpness, Basil was basically a kind and generous man.”[8]

This was a sentiment that seemed to have been shared by people who dealt with Dean on a more personal level than a purely professional basis. Those working closely with him during the stressful war years at Drury Lane knew another side of him.

It’s easy to forget in our polarised social media-driven world that more than one thing can be true at the same time. Virginia Vernon, who was a friend of Basil before working for him as Chief Welfare Officer at ENSA summed up this complex character well:

‘Basil Dean was a hat-trick: dictator, artist, and human being.’[10]

He was obviously driven, a perfectionist, and had a phenomenal work rate, but Naomi Jacob thought his hard shell hid a more vulnerable side and he was sometimes over-compensating:

“I should say that in all probability Basil Dean is terribly shy. That kind of shyness which makes you self-assertive, that kind of inability to say what you really want to say because you are afraid that people will think you “soft”.”[11]

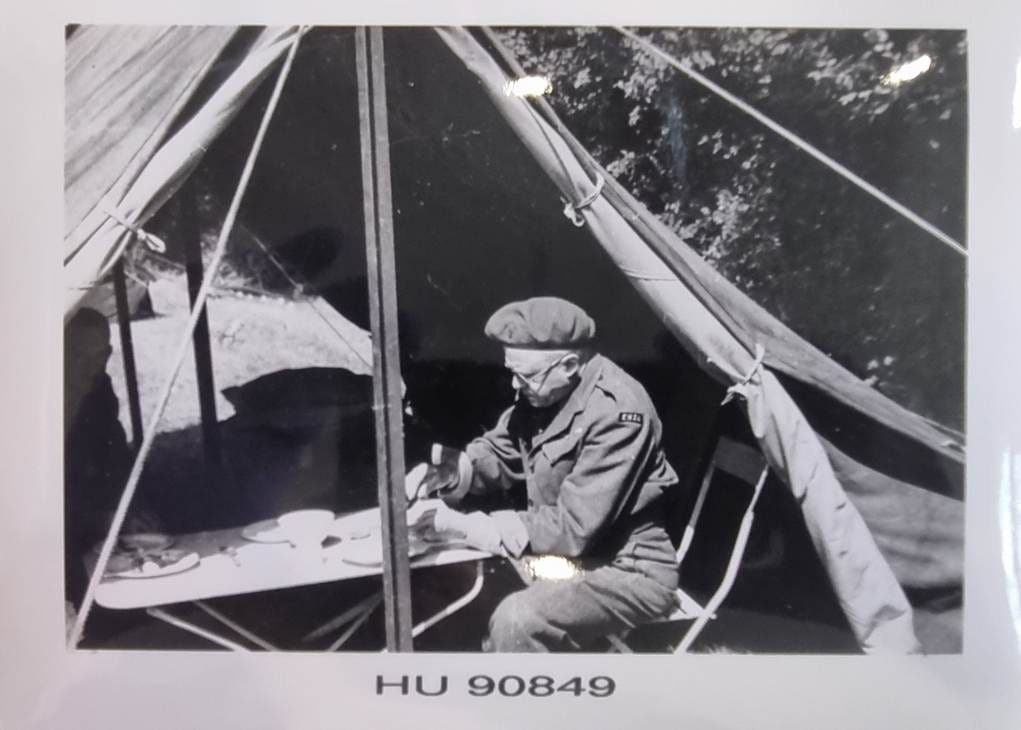

My favourite photo of Basil Dean is this one taken in August 1044 at the ENSA camp just outside of Bayeaux busy at work in his tent.

He seemed to be in his element in this photo. After all, Dean was an old soldier, having been instrumental in setting up Garrison Theatres to entertain the troops in the First World War.

Dean’s steely, single-minded belief in his cause – to harness entertainment to raise morale – led him into many conflicts with others. Before the war, he published a pamphlet on the role that the entertainment industry could play in a future conflict. He tirelessly lobbied the government in 1939 to formally recognise the theatre as a reserved occupation and view it as a form of national service. It didn’t quite happen like that, but through the NAAFI, ENSA gained a quasi-official status in September 1939 and oversight from the Treasury from 1941. This crystal clear vision helped him push on through the seven years of ENSA’s history. Richard Llewellyn, Dean's assistant during the war, described him as:

‘a monolith, a kindly—sometimes—tyrant, a bully … But his was the influence, the hand on the wheel, that never faltered'[12]

To mix metaphors, Dean’s forceful “The Curtain Must Go Up” attitude was needed when dealing with some of the people in the War Office.

At various points during the war, Dean was in conflict with the NAAFI, the Army Welfare Service, the War Office, the Ministry of Labour, the House of Commons, and the USO. Not to mention, the unions, commercial theatre owners, Hollywood stars, and cinema operators. Perhaps the only group that didn’t come into direct conflict with Dean during the war was Germany.

Dean’s life was a long battle, and he was probably happiest during the war. In his autobiography, Theatre at War, he attempts to tell the story of the entertainers who served their country and defends himself and ENSA against the criticism they received. His brusque manner put many a nose out of joint, as can be seen from this diplomatically worded note by a Secretary from the Treasury:

“I am afraid that Mr Basil Dean himself rather tends to trail his coat on occasion. For example, the War Office view is that the soldiers should as far as possible provide their own entertainments from their own ranks and Basil Dean counters this by saying that there are limits since a Unit soon gets tired after a few performances of the same concert party drawn from local talent and that it would be improper for the Army to send their own soldiers ‘on tour’ to give entertainments and he dragged this point in to his speech at the recent ENSA luncheon and again in his broadcast talk last Sunday.”[13]

Whether Dean was always looking for a fight, as the quote suggests or simply didn’t care what got in the way of his single objective, he tried to overcome anything that got in his way. He annoyed the War Office when he flew out to the Middle East in 1943 and told the Army Welfare staff how they should manage film distribution.[14] Dean created his own D-Day Dodgers situation before Lady Astor by publishing an article in The Times crowing about how much entertainment was being sent to Normandy at a time when ENSA was making excuses not to send performers to Italy. There was also bad feeling from some in the entertainment industry and even the Government that Dean had a broader land-grabbing agenda. In minutes discussing appointing Dean to the National Services Entertainment Board in 1941, these suspicions are clearly stated:

“I think I ought to add that I am still under the impression that there is considerable suspicion of Mr Basil Dean, in the sense that they believe he would like to control the entire industry, and that this is one of the matters which gives rise to most of the difficulty.”[15]

The prosecution of the war kept a lid on this kind of resentment, but in September 1945, the ENSA lid flew off with a series of very public resignations. The Rev Dunnico accused Dean of being a dictator, but far more damaging, he suggested financial impropriety. The British Press had a field day:

Dean responded with his own headlines, for example, “Dictator? Not I, Dean” - Daily Herald 4th Sept 1945, defending his name with:

“During the war the demand for quantity has outweighed the restrictions of quality, but ENSA is reorganising its operations to meet the changed circumstances.”

However, this was fast turning into more than a tit for tat. With the accusation of mismanagement of public funds, the Treasury was suddenly placed in a very awkward position, with a public enquiry being demanded in Parliament. Minutes from a Treasury meeting during this period highlight their nervousness:

“It is clear that there is a good deal of feeling against Basil Dean amongst other members of the entertainments profession, and it is a pity that ENSA was not set up originally on a proper basis. If it had had a council fully representative of the entertainments profession and if Basil Dean had been the servant of this council rather than an effective dictator, the troubles would have been minimised and if the worst came to the worst one could have looked to the council for the provision of a new director if Basil Dean went. Basil Dean’s dictatorial tendencies, and the feeling against him, seem to me to be a definite weakness to us in maintaining the present arrangements.”[16]

This formal organisational structure and oversight is what Dean had lobbied the Government for in 1939, but was ignored. The Treasury managed to get the lid back on the ENSA pot without a public enquiry, but this incident meant that their days were numbered.

Basil Dean was a diffident, shy man who had created an entertainment empire before the war and continued to do so during it as well. That wartime empire was founded on a very worthy cause: the entertainment of the troops. He sums up his achievements with ENSA in his memoir:

“Such a mobilization of entertainment had never before been seen, and never will be again; just as well that it should be so, for the demand grew beyond manageable proportions, so that mistakes were made, and the quality sometimes fell short of expectation.”[17]

A remarkable man. Perhaps a bastard, too.

[1] Andrew Merriman, Greasepaint and Cordite: The Story of ENSA and Concert Party Entertainment during the Second World War (Aurum, 2012), p. 5.

[2] ‘T 161/1457 Treasury: Supply Department Registered Files (S Series)’, fol. 2, T 161/1126.

[3] Oliver Soden, Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2024), p. 30.

[4] Soden, Masquerade, p. 166.

[5] Eric Ambler, Here Lies: An Autobiography (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1985), p. 188.

[6] Jack Hawkins, Anything for a Quiet Life: The Autobiography of Jack Hawkins, 1st Edition (Elm Tree Books Ltd, 1973), p. 28.

[7] Joyce Grenfell, Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure, First (Macmillan London Limited, 1976), p. 288; David Bret, The George Formby Story (Amazon, 2022), p. 51.

[8] Hawkins, Anything for a Quiet Life, pp. 29–30.

[9] Basil Dean, The Theatre at War (George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, 1956).

[10] ‘IWM Documents.7473: Virginia Vernon Diaries’, Documents.7473: Virginia Vernon Diaries.

[11] Naomi Jacob, Me and the Mediterranean, First Edition (Hutchinson & co., ltd, 1945), p. 26.

[12] From Basil Dean’s biography in https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-31016?rskey=m7WJiQ&result=1

[13] ‘T 161/1126 Treasury: Supply Department Registered Files (S Series)’, fol. 7, T 161/1126.

[14] ‘ADM 116/4971 Services Committee for the Welfare of the Forces Minutes of Meetings’, ADM 116/4971 Services Committee for the Welfare of the Forces minutes of meetings.

[15] ‘LAB 26/43 National Services Entertainments Board’, LAB LAB 26/43.

[16] ‘TNA T 161/1126 Treasury: Supply Department Registered Files (S Series)’, fol. 6, p.34.

[17] Dean, The Theatre at War, p. 17.