Following on from my previous post on Arnhem, I spent last week in Holland with a few days visiting Oosterbeek and that famous Bridge. Whilst there, I also read Al Murray’s excellent account of the turning point of the battle for Arnhem, Black Tuesday.[1] Here are some thoughts after walking the ground.

Arriving by bus from the few miles journey from Arnhem to the Airborne Museum at the Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek, I was immediately struck by the importance of this operation to the residents. Almost every house along the way were displaying the maroon and sky blue colours of the 1st Airborne Divisions flag. In his book, Murray talks about how an unknown Dutch woman who insisted on staying to help the wounded at the Schoonoord explaining that it was her duty to treat those who were liberating her country. This same sense of duty is still evident today in the Pegasus flags covering Arnhem and the surrounding villages.

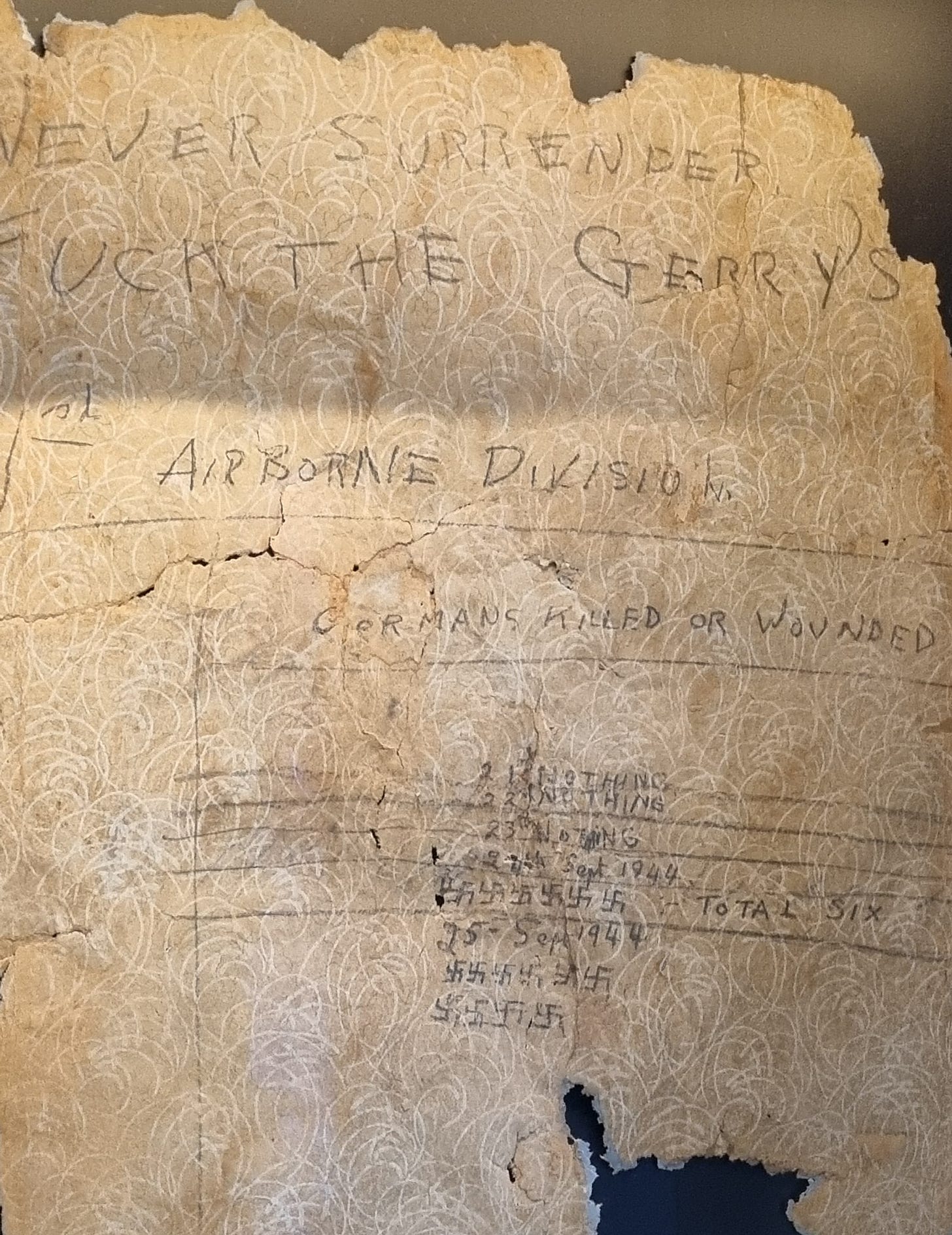

The Hartenstein is one of the best museums I’ve visited with an audio tour provided by Anthony Beevor. In addition to the usual exhibits, the Airborne museum included a special display about the St Elisabeth hospital and it was fascinating to learn about the German sisters who were served there alongside Dutch and British medical staff there. Among the artifacts left after the battle, was a strip of wallpaper where the paratroopers chalked up their tallies whilst defending the shrinking perimeter, with the words, ‘Never Surrender’:

I walked the perimeter around the Hartenstein Hotel following this trial: https://en.visitarnhem.com/routes/3023717345/perimeter-route. Past the mortar pits in the now peaceful woods with herds of deer, where you can still see the depressions in the earth. Following the track to the south to the Old Church, where Major Lonsdale gave his rousing speech to his troops as re-enacted in the movie, Theirs Is the Glory. If this point had not been held, the Allies would have been surrounded and would not have been able to retreat across the Neder Rhine in Operation Berlin. Then walking back north past Hotel De Tafelburg, formerly General Model’s HQ, and the Schoonoord, a temporary medical centre during the battle and now a very popular bar and restaurant. Whilst it’s a relatively small geographical area on a map (Murray mentions that the pocket was so narrow that the German artillery was often in danger of overshooting and hitting their own men), I found it larger than I had expected. I was also struck by the sheer number of Allied troops who became trapped in the village, not to mention the 6,500 troops who ended up as prisoners of war as they ran out of ammunition, food, and water.

The British love their heroic defeats, so it’s no surprise that Arnhem holds such a fascination for us. We will continue to cynically ask whether the investment in all those expensive airborne troops could have been spent elsewhere, whether Operation Market Garden was merely one of Monty’s vanity projects, and whether it was always doomed to fail. But visiting Arnhem 80 years on and seeing how the Dutch locals have remembered the bravery of the men who gave them hope, fought for their freedom, and tried to liberate their country, makes all those questions seem irrelevant. The failure of the Allies to capture the final bridge across the Rhine in September 1944 had a devastating impact on the Dutch civilian population who lost their homes and suffered through the Hongerwinter famine over the subsequent 8 months. Knowing all this makes their acts of remembrance even more poignant and is summed up in the Airborne Monument at Oosterbeek.

The following is written on the plaque at the Airborne Monument explaining the feelings of the local population and why they still remember:

“But their hearts still cherished the memory of these gallant British soldiers who had also fought and died for the sake of Holland's freedom. And when the inhabitants of Oosterbeek returned home once again, of their own accord they decided to build a memorial as a token of their homage, their admiration and their gratitude: A proud Monument was erected near the Hartenstein Hotel, the place where General Urquhart and his staff led the resistance during the ten-day battle. Its massive and symbolic structure preserves the memory of a struggle so heroic and so furious that it will never be forgotten. The scenes on the sides of the Monument represent the landing (East) the women of Oosterbeek caring for the wounded (South) the Dutch resistance forces co-operating with the Airborne troops (West) and the last heroic stand (North). The lofty column is surmounted by five figures, the figure of Freedom rising above the others, who take the form of soldiers and civilians, the upholders of freedom. Faith, righteousness, hope and love, and the home-these are the thoughts and ideals that are symbolised in stone. And that is the monument which stands in a fine park, the monument that the people of Oosterbeek presented to General Urquhart. Its stones will bear lasting witness to what lives on in hearts of everyone in Oosterbeek. Admiration and honour for the heroes of the First Airborne Division who fought and died here in the cause of Freedom.”

[1] Al Murray, ARNHEM: Black Tuesday (S.l.: BANTAM BOOKS, 2024).